Let’s Talk: RECYCLE- Expanding Wastewater Purification Program

a 4-R Integrated Approach to water management Series nOV 23, 2021For more than a century, the environmentally disastrous and economically costly practice of 'pump-and-dump' – where we expend tremendous resources bringing water from hundreds of miles away simply to treat it, use it once, and then discharge it into our waterways - has defined California's water planning. In the case of wastewater, we go the extra step of treating it again to nearly drinkable standards, only to send it directly into our rivers and coastal waters. This approach is expensive, wasteful, and harmful to our local environment. It is time to take the 'waste' out of wastewater.

As drought becomes our new normal, we need to rethink our current wasteful practice and recognize that recycled wastewater offers a tremendous opportunity to make LA more water secure. In our last blog, we discussed the potential of reuse, turning stormwater from liability to asset, and today we'll be diving into the 3rd R of our approach, Recycle. So, let's dive into why expanding our current (and successful) wastewater purification programs can lead to a more sustainable and water-independent region.

What is wastewater recycling and how much of it are we already doing?

Wastewater reclamation process. Graphic courtesy of Orange County Water District.

Simply put, wastewater reclamation (or 'Recycling') is a strategy to use highly advanced treatment technologies to purify wastewater so that it can be beneficially reused and thus reduce our dependence on imported water. While technologies can differ to some extent, wastewater reclamation usually consists of microfiltration, reverse osmosis, and ultraviolet light. After such treatment, this treated water is actually purer than our current water supplies.

Recycled water can be for potable uses such as drinking water, or for various non-potable uses, including irrigation of homes and parks or industrial processes, which can sometimes require even higher quality water than drinking supplies. Even when recycling water for potable uses, there are two different approaches. Indirect potable reuse (or IPR), which is currently allowed and regulated in California, means after purification, the recycled wastewater is injected into our groundwater basins (as being proposed in LA) to mix with existing supplies before being treated again and sent to customers. Direct potable reuse ('DPR'), which currently has not been permitted in California, means skipping the groundwater injection and sending purified water to a holding system before going through our existing drinking water treatment facilities. The State Water Board is currently developing regulations for DPR, slated for completion in 2023.

Direct potable reuse, soon to be an option for California’s treatment plants, does away with the need for an environmental buffer — a reservoir, storage tank, or underground aquifer — to filter water before it goes to consumers. Photo credit: Inspired by Water Resources Research Center at the University of Arizona PDF, from Dave Gandy / Wikimedia (CC BY 3.0), Clker-Free-Vector-Images / Pixabay, and OpenClipart-Vectors / Pixabay

Of course, wastewater recycling is not new. Since 2008, our neighbors to the south in Orange County have been recycling up to 100 million gallons of wastewater a day, which is enough to serve 850,000 residents, at their Groundwater Replenishment System (and the origins of this effort started more than forty years ago!). Fairfax County, Virginia, has been relying on recycled wastewater from the Occoquan Reservoir since 1978. Nearly 40% of Singapore’s water is supplied by purified wastewater, which they have dubbed NEWater. And in 2013, Big Spring, Texas, became the first city in the U.S. to put a DPR project online, following suit with an additional facility a year later. And these are just a few of the hundreds of wastewater recycling projects across the globe. In fact, we have similarly been recycling wastewater in the LA Region, in some cases for decades.

What does LA's current wastewater system look like?

As massive as the LA region is, it is of little surprise that nearly a billion gallons of sewage runs through almost 10,000 miles of pipes and is treated at more than a dozen wastewater plants every single day. There are two major wastewater systems in the region, as well as a few smaller plants.

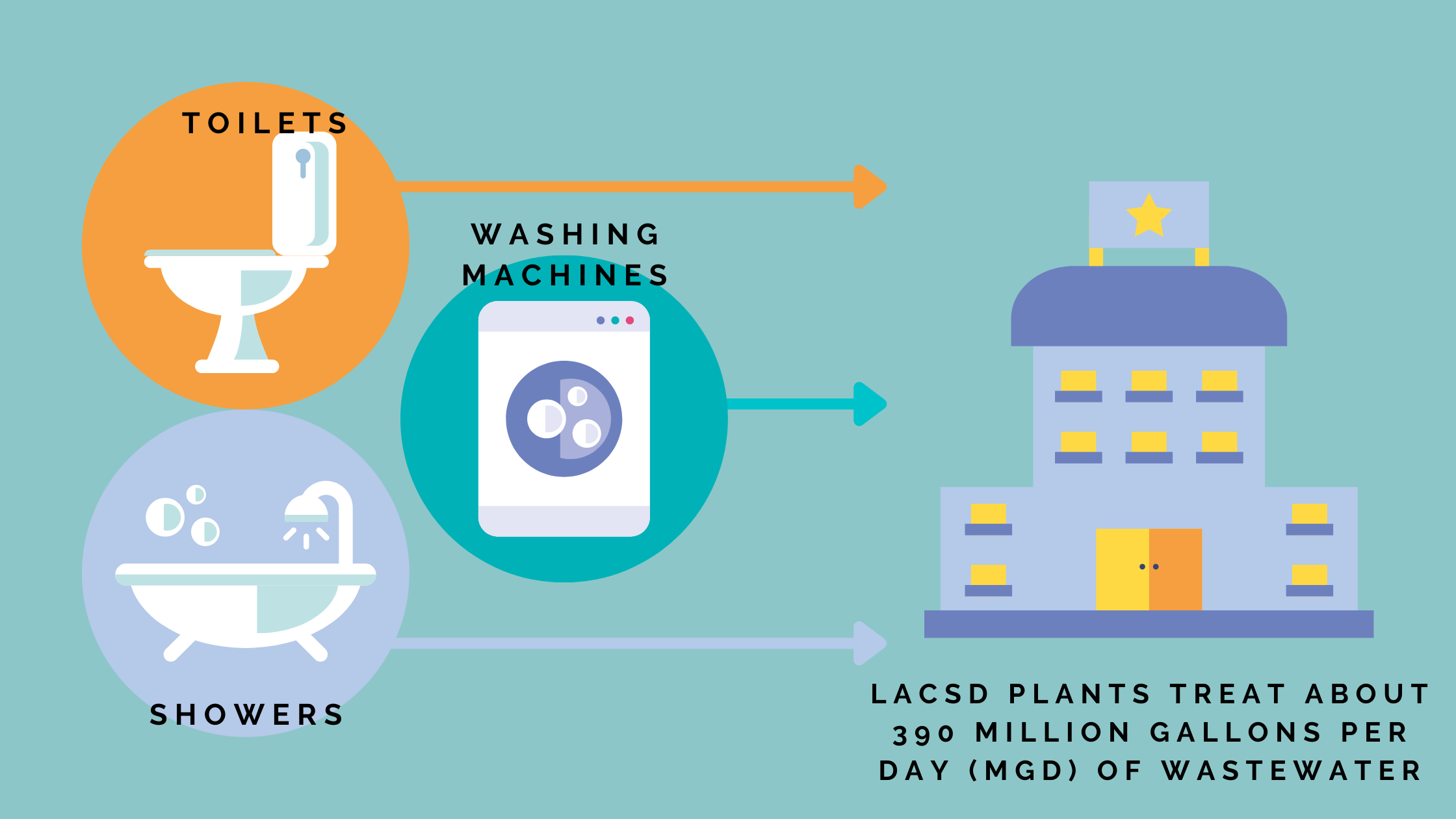

The Los Angeles County Sanitation Districts (LACSD), which consists of 24 separate water districts, operates one of the world's most extensive wastewater treatment programs. With its 11 wastewater reclamation facilities, LACSD serves approximately 5.6 million users in 78 cities and unincorporated county areas across the greater Los Angeles region. Combined, these plants treat about 390 million gallons per day (MGD) of wastewater from our homes, including toilets, washing machines, and showers. LACSD facilities already produce 90 million gallons per day of recycled water that is beneficially reused at over 900 locations, including groundwater replenishment at the Montebello Forebay Groundwater Recharge Project, outdoor irrigation, agriculture, and industrial water supply. In fact, over the last 50 years, the Sanitation Districts have been the nation’s largest producer of recycled water.

In partnership with other local municipalities, the City of Los Angeles operates an even larger system (at least by miles of pipe). These treatment plants ultimately feed into the Hyperion facility in El Segundo, treating nearly 400 million gallons of wastewater a day. Like LACSD, LA Sanitation (LASAN) is also already recycling a significant amount of wastewater, including providing source water for West Basin's Edward C. Little Water Recycling Facility, which has produced over 200 billion gallons of recycled water over the past 25 years.

However, even with these impressive efforts, only about 10% of the LA region's water supplies are provided by recycled wastewater. Worst yet, we are still discharging nearly 500 million gallons a day of treated wastewater — enough to fill the world-famous Rose Bowl nearly five times — into the ocean, where it serves no beneficial uses.

Rose Bowl in Pasadena, CA. Photo by Ted Eytan

This wasteful approach is why LA Waterkeeper filed and won a landmark victory in our ‘Waste and Unreasonable Use’ (WUU) litigation, which we’re currently defending in appeals court. As outlined in detail in our previous blog, LA Waterkeeper brought this groundbreaking challenge under Article X Section 2 of the California Constitution, which prohibits waste or unreasonable use of the state’s precious water resources, to push our wastewater agencies to do better. And Judge Chalfant agreed, noting that large wastewater agencies in drought-stricken Los Angeles should explore ways to maximize reclamation and reuse.

Luckily, our water agencies are getting the message and changing course. In 2019, Mayor Garcetti committed to having the City recycle 100% of its wastewater by 2035. The partnership between LASAN and LADWP, known as OperationNEXT, is moving forward and could result in 170 MGD-180 MGD of reclaimed water in the next 15 years. At the same time, the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California – a long time champion for importing water - is now partnering with LACSD on the Regional Recycled Water Program (RRWP), which seeks to reclaim 150MGD of wastewater, with capacity for even more recycling in the future. These two efforts, which would represent the most extensive recycling programs globally, combined with smaller recycling efforts also underway, would mean that the LA region could meet more than a third and maybe 40% of its water needs from recycled wastewater.

What’s next with wastewater recycling in LA?

LA Waterkeeper has long supported wastewater reclamation as part of our 4R strategy, including support for OperationNEXT and the RRWP (for which we’ve provided regular testimony and served on advisory committees). Transforming our aging wastewater treatment infrastructure into a state-of-the-art reclamation system offers a load of benefits. Beyond making the region significantly more water secure, it does so in a relatively energy-efficient and cost-effective way (at least compared to pouring billions of dollars into tunnels, dams, and diversions that double-down on our outdated pump-and-dump approach to water management). It will enhance our marine environment while generating tens of thousands of construction and operations jobs – a much-needed boon for the local economy. And investment in wastewater recycling – despite significant up-front capital costs – can ultimately save money by reducing water imports, eliminating the need to fund costlier water supply projects, providing greenhouse emission reductions, and reducing environmental harm and mitigation payments. So while the upfront investment can be significant, water recycling pays for itself over a reasonably short time horizon.

Orange County have been recycling up to 100 million gallons of wastewater a day, which is enough to serve 850,000 residents, at their Groundwater Replenishment System.

While we support wastewater recycling, it’s essential to recognize that a lot still must happen for these projects to come to fruition, and our support is not unconditional. In general, we favor most of this water to be used for potable uses through IPR and, eventually, DPR. But building a new network of ‘purple pipes’ that deliver relatively small volumes of water for residential lawns, while better than using imported water for those uses, is expensive and can unintentionally undermine efforts to convert those spaces to native and drought-tolerant vegetation or install rain gardens in homes.

Delivering recycled water to larger public spaces like parks is better than home delivery, but the same dynamics apply – can we be lessening those water needs or meeting them with more localized solutions like water capture? Even in industrial uses, it is critical to ensure that power plants, refineries, or other large users operate as efficiently and sustainably as possible before providing them with precious recycled water.

Older man watering his garden. Photo by Laney Smith.

Ensuring a stable supply of potable water is still the most efficient and best use of reclaimed water. But, of course, in doing so, all steps must be taken to guarantee that safeguards and redundancies are put in place to ensure such recycled water is safe. We believe adopted regulations will require such approaches, and it is also important to note that LA’s current water supply is largely recycled and treated already. In fact, hundreds of millions of gallons of wastewater discharge a day, including agricultural and urban runoff and industrial pollution, already go into the Colorado River, the Bay-Delta, and other places from where we get our current supplies. But, again, all of this is treated before safely reaching our homes and businesses.

Lastly, we would like to see our water agencies explore options to minimize the piping and pumping of recycled wastewater – both expensive and energy-intensive – to the maximum extent possible.

In short, our preference should be to collect, purify and deliver water as close to the source and ultimate customers as possible. This could be done:

Los Angeles- Glendale Water Reclamation Plant. Photo via LA Sanitation.

by upgrading wastewater infrastructure that is part of our existing system (such as the 11 plants that make up the LACSD system or four that comprise LASAN’s Hyperion network) to expand reclamation capacity;

by ensuring that all the region’s water agencies – particularly LACSD and LASAN – are coordinating to provide existing and planned infrastructure is used as efficiently as possible;

and even by considering building new smaller reclamation plants closer to the source of the wastewater and ultimate customers.

Of course, there are ways to decentralize wastewater at an even smaller scale (home, business, neighborhood), which we believe should be explored and pursued where possible. At a minimum, though, Operation NEXT and the RRWP must explore ways to decentralize their projects to the extent possible. If there is one lesson we can take from the Hyperion spill that occurred on July 11, in addition to the need to upgrade our facilities to state-of-the-art wastewater reclamation plants, it's that sending our wastewater long distances and relying on a small number of treatment plants can have potentially disastrous results.

What can YOU do?

While much about expanding the use of recycled water is beyond individual actions, everyone can play some critical steps in improving our wastewater treatment processes, which can prevent sewage spills now while making wastewater reclamation easier in the future.

Whether at your home or business, know what you should and shouldn't flush. Things like flushable wipes, paper towels, menstrual products, diapers, condoms, dental floss, fats, oils, or grease can combine to clog our wastewater system and undermine treatment processes. And items such as medications, cleaning products, pesticides, herbicides, paints, and other household hazardous waste are difficult to treat, meaning they end up polluting our waterways while sometimes even damaging treatment facilities due to their corrosive or toxic nature. Lastly, as our friends at San Francisco Baykeeper have outlined, make sure the sewer lines near your home or businesses are regularly inspected, free of intrusion (such as from tree roots), and are in good operating order.

While there are important steps you can take in your actions, the most important thing you can do is continue to get educated on wastewater reclamation and make your voice heard. Let your water agencies, elected officials, and other decision-makers know that you support moving towards a wastewater recycling future for the LA region that is done as expeditiously but safely as possible and in a way that minimizes costs and environmental impacts.

CA coast. Photo by Ari He.

The bottom line is LA has a strong foundation for water recycling. We are already doing the hard part of taking all the wastewater and treating it (only to dump it into the ocean). However, it's time to take our programs to the next level for the sake of our changing climate, our dwindling water supplies, our coastal environment, and our burdened communities.

Up next in our 4-R approach is Restore. How is remediating contaminated groundwater supplies a critical component of a sustainable local water supply for Los Angeles? And what is LA doing to restore our groundwater? Stay tuned as we dive into the 4th and final ‘R’ of our Integrated Water Management Approach, Restore.